MÄGI, TCHAIKOVSKY, RACHMANINOFF

Notes on the composers and the pieces

Ester Mägi

Bukoolika (Bucolic)

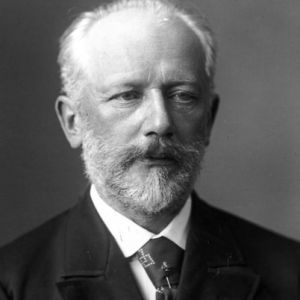

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 23 (Second Edition, 1879)

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Symphony No. 3

Return to Home Page |

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 23 (Second Edition, 1879)

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) was Russia’s first truly professional composer and the first to achieve fame outside Russia. He was also the link between the Russian school and the Austro-German tradition, paving the way for Glazunov, Miaskovsky, Taneyev, Kallinikov, and others. In his youth, his parents supported his musical interests, but poor employment prospects as a musician induced them to enroll him in St. Petersburg’s School of Jurisprudence to study law. When it was time to begin his studies, the boy’s mother accompanied him to St. Petersburg, where they saw Mikhail Glinka’s Life for the Tsar. After she returned home, loneliness traumatized Piotr, as would her death four years later, but he managed to graduate and take a job as a civil servant. He never forgot Glinka’s opera, though, and the memory induced him to pursue music as well. He studied theory with Nikolai Zaremba, piano and composition with Anton Rubinstein at the Russian Musical Society (RMS, which became the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1862). After graduation, he taught at the RMS in Moscow and established ties with a group of composers known as the “Mighty Five”: Mily Balakirev, Cesar Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Alexander Borodin. His first symphony was performed in 1868, but his breakthrough work was Romeo and Juliet (1870, rev. 1880).

In 1876, Tchaikovsky began a platonic relationship with Nadezhda von Meck, a wealthy widow and supporter of the arts. Von Meck was so impressed with his music that she paid him a yearly stipend until 1890 when financial problems forced her to stop payments and eventually end their relationship. The composer was well enough off financially by then to take care of himself, but the cessation of those payments was an emotional blow.

Tchaikovsky was almost certainly homosexual, and the struggle to keep that private probably produced the inner turmoil that comes through in many of his works. His engagement to Belgian soprano Desirée Artot fizzled without serious consequences. In 1877, he married Antonina Miliukova, an unbalanced former student, perhaps hoping the marriage would hide his homosexuality. Their union proved disastrous, however, and he soon fled Russia for Switzerland and Italy. The two were never divorced, and he long feared that Antonina would expose his homosexuality. While away from Russia he finished Eugene Onegin, Symphony No. 4, and the Violin Concerto.

In 1884, Tsar Alexander III awarded him a lifetime pension and the Order of St. Vladimir. In 1887, the composer became associated with the Belyayev Circle (after Mitrofan Belyayev, a Russian industrialist and supporter of the arts) a larger, more influential successor to the Five and more tolerant of Western musical practices. He also went on a conducting tour of Europe where his music was well received. After he returned home, he began his fifth symphony. For a while he felt “played out as a composer,” but he completed the symphony in 1888, followed by Sleeping Beauty (1889), Queen of Spades and Souvenir de Florence (1890), and Nutcracker and Symphony No. 6 (1893). Nine days after conducting the Sixth he died at age 53. Debate persists as to whether he succumbed from drinking contaminated water during a cholera epidemic or committed suicide.

Tchaikovsky finished the Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1875, but his plan for Russian pianist and conductor Nikolai Rubinstein to play the premiere was thwarted when Rubinstein refused to play it as written. The composer vowed not to “change a note” and dedicated the work to a grateful Hans von Bülow who played its premiere in Boston. Gustav Kross gave the Russian premiere in a performance that Tchaikovsky called an “atrocious cacophony.” Far better was its Moscow premiere played by Sergei Taneyev with Rubinstein, who had done a turnaround about the piece, on the podium. The composer eventually conceded that the concerto could be improved and produced a second version in 1879 that made the piano part richer and easier to play.

The 1879 edition was the score Rubinstein used whenever he performed the work as a pianist and conductor, and it was the edition Tchaikovsky used when he conducted the work. The 1879 score was the composer’s last word on the subject, but it is not the edition that we hear in today’s concert halls. Pianist Alexander Siloti (1863–1945)—a student of Tchaikovsky and Franz Liszt and champion of Sergei Rachmaninoff—and probably others produced a third version in 1889, most likely without Tchaikovsky’s approval. Tonight the Mercury Orchestra will play the 1879 score.

The differences between the second (1879) and third (1889) versions are significant. The second is early Tchaikovsky and tends to look back to the Classical era. The third is a product of a younger musician working in the Romantic era. According to pianist Kirill Gerstein, who recorded the 1879 score, there are “maybe four or five significant changes and [over 100] minor discrepancies of articulation and dynamic indications…. The 1889 score is warmer, fuller, and more Romantic than 1879…there’s a sort of romanticized legato slurring, but what Tchaikovsky [wanted] is a certain portato declamato with many small differences of articulation in the orchestral parts.”1 The most obvious change is in the introduction where the original opening arpeggio piano chords become solid blocks followed by a new languorous melody. In the second movement scherzo section, the Allegro vivace becomes a hurried Prestissimo, and there is a cut in the middle of the third movement. Referring to the end of the second subject of the third movement, Gerstein writes that the “big octave jumps, ritenuto molto and a fermata before the tutti” are not in Tchaikovsky’s score, which instead contains “neighboring octaves…that flow into the big tune without a pause.” The ending exchanges 1879’s lyricism for a big, triumphant conclusion. Other changes are minor and less noticeable.

The first movement’s introduction begins with a heroic call to arms by the horns followed by a lyrical melody in the strings. Neither is heard again, but Russian musicologist Francis Maes writes: “The opening melody comprises the most important motivic core elements for the entire work, and the themes of the three movements are subtly linked thereby creating a unity of construction.” The movement proper begins with what is apparently a Ukranian folk song (Theme I); the response is another lyrical melody that may be a French folk song (Theme II), and a peaceful Theme III follows. The development presents the usual solo technical display, and the orchestra writing is even stormy in one section. An exciting recapitulation works with I and II followed by a piano cadenza and a stirring, triumphant coda.

The second movement is in ABA form. A reflective Theme A is played by the flute, and the piano responds with the theme. Two flutes play a playful figure followed by Theme B in the winds. After some playful pianism, the theme reappears in the cello then the oboe. B is marked Allegro vivace or Prestissimo depending on the edition. The piano plays a technical passage followed by an odd new melody in the strings. The piano returns with extended passgework then returns quietly to Theme A, which is picked up as a variant by the oboe and horn, and the movement ends while hinting at A in a quiet coda.

The third movement plays with two themes, each heard three times. The first is based on another Ukranian folk song and is played mostly by the piano. The second is played the first and second time in the strings and after a long interceding passage, by the piano and orchestra before a triumphant conclusion.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra. He is a former member of Bay Colony Brass (where he was also the Operations/Personnel Manager), the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony, as well as trombonist and orchestra manager of Lowell House Opera, Commonwealth Opera, and MetroWest Opera. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. His fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

____

1 Jeremy Nicholas, “Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto: Kirill Gerstein tells Jeremy Nicholas how a new edition is closest to the composer’s intentions,”

Gramophone, Feb. 2015, Vol. 93, #1119.

|