RAVEL AND MUSSORGSKY

Notes on the composers and the pieces

Maurice Ravel

Alborada del gracioso

Maurice Ravel

Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

Modest Mussorgsky

Pictures at an Exhibition

Return to Home Page |

Maurice Ravel: Alborada del gracioso, from Miroirs

Maurice Ravel: Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

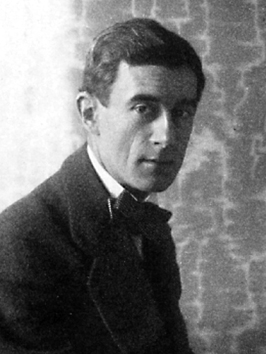

Joseph Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) was born in the French town of Ciboure, near Spain, to a Swiss father and Basque mother. The family moved to Paris when the boy was three months old, and he spent most of his life there. His parents supported their son’s musical ambitions, but his independent nature made schooling difficult. Later, he entered the Paris Conservatoire but was expelled for lack of promise. After turning to composition, he re-enrolled as a student of Gabriel Fauré, but academic problems led to his expulsion over Faure’s objections. Fauré then allowed the young man to audit his class, and the two remained friends.

Ravel was a dapper, meticulous, and precise man, though in 1900 he found conviviality with a feisty group of artists known as Les Apaches that included Manuel de Falla, Florent Schmitt, and Igor Stravinsky. A political liberal, he was not religious, and though a patriotic Frenchman, he was not blind to his countrymen’s foibles: while at the front, he opposed bans on German music in France. He wrote excellent, often biting, criticism, and he recognized Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps and Debussy’s Pelléas et Melisande for the groundbreaking works they were. He was not known as a pedagogue, but Ralph Vaughan Williams gave him credit for teaching him the fine points of orchestration.

Ravel composed his first successful work, Jeux d’eau for piano, in 1901. That same year he embarked on the first of five unsuccessful attempts to win the Prix de Rome for Musical Composition only to come in second at best. His last failure ignited l’affaire Ravel, a public protest over unfairness to a recognized composer in the face of generational conflict and the fact that all finalists were students of a Paris Conservatoire professor on the jury. Several Conservatoire professors resigned, and Conservatoire president Theodore Dubois was replaced with Fauré. (To be fair, Ravel violated some competition rules, so his fate may not have been entirely unjustified.) His last try was in 1905 after his String Quartet and the song cycle Shéhérazade had established him as a composer.

After l’affaire, Ravel completed Introduction and Allegro, Sonatine, and Miroirs. From1909 to 1913, he was occupied with Daphnis et Chloé, Valses nobles et sentimentales, Ma mere l’oye (Mother Goose), and Trois poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé.

When the Great War broke out, Ravel tried to enlist as a soldier but was rejected for physical reasons. He did see action as a truck driver until health issues forced a return to Paris where the war, ill health, and his mother’s death drove him into a depression. After discharge, he underwent surgery and moved around quite a bit until he regained his equilibrium in 1921. He had not been idle though. Those years produced Le tombeau de Couperin, La valse, and the orchestration of Alborada del gracioso for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

Ravel admired Bach, Mendelssohn and Schubert, and was heavily influenced by Mozart, Chabrier, Saint-Saëns, Satie, Rimsky-Korsakov (whose orchestration fascinated him), Gershwin, and American jazz. He is often associated with Debussy. Both are thought of as Impressionists, a description each denied. (Ravel applied the term only to painting.) In fact, he was a Classicist who precisely shaped melodies, rhythms, and structures while sometimes employing Impressionist techniques. “The most perfect of Swiss watchmakers,”Stravinsky called him. In fact, Ravel rarely used the whole-tone scale (as Debussy did). He preferred modes, particularly those close to major and minor, and he favored extended chords like ninths and elevenths, often dividing the strings to create them and avoided leading tones. A brilliant orchestrator, he considered orchestration a vital part of composition. Many of his orchestral works are rescorings of his piano music. He also orchestrated works of other composers, most notably Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. He even considered reworking Debussy’s La mer.

Alborada del Gracioso began life as part of Miroirs whose movements are each dedicated to one of Les Apaches, a group consisting of Ravel and friends who opposed established artistic traditions. Alborada, the fourth movement of Miroirs, is dedicated to musicologist and critic Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi (who wrote a biography of Modest Mussorgsky). Alborada del gracioso—loosely, Funny Dawn, Morning Song of the Jester, or The Clown’s Aubade—refers to a stock character of Spanish theater. The first of Ravel's “Spanish” works, it was followed by Rapsodie espagnole and L’heure espagnole. Ravel orchestrated Alborada del gracioso in 1918 for Sergei Diaghilev, who used it in his ballet Les jardins d’Aranjuez. The work opens with a lively dance of pizzicato strings that gives way to woodwind solos. Suddenly, the whole orchestra barges in with a lively dance until things come to a halt. There follows a serenading bassoon representing a sad clown singing and often interrupted by breathy exotic string chords and finally leading to a triumphantly colorful ending.

Ravel worked on his two piano concertos between 1928 and 1931. The one in G Major, written for pianist Marguerite Long, was a three movement work of an upbeat, sometimes jazzy nature. “My only wish…was to write…a brilliant work, clearly highlighting the soloist’s virtuosity, without [needless] profundity,” he said.

His Piano Concerto for Left Hand in D Major was another matter entirely. He wrote it for pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who lost his right arm in World War I and responded by commissioning left-hand piano concertos from Richard Strauss, Franz Schmidt, Erich Korngold, Karl Weigl, Aleksander Tansman, Sergei Prokofiev, and Benjamin Britten. By the time Ravel began his left-hand concerto, he was also working on the G Major, but the mood of “Left Hand” is the diametric opposite. Making the composer’s task more difficult was his wish for the D Major to sound like a two-hand concerto. One of the work’s difficulties is that the pianist must often play a theme and accompaniment at the same time with one hand.

The Concerto begins with stirring in the depths of the orchestra as the cellos play sustained notes over flowing arpeggios in the string basses. Primeval rumbling in the contrabassoon and basses soon gives way to a haunting horn passage that leads to what sounds like a sunrise culminating in a huge chordal climax. The piano’s dramatic entrance begins with a long, emphatic passage that Wittgenstein disapprovingly compared to a cadenza. (It is more dramatic and thematic than that.) A broadly phrased orchestral passage replies with a passage that restores the opening dark mood. Later, the orchestra plays with a sparkling piano. A march soon breaks out in the orchestra accompanied by sparkling hijinks in the piano. The bassoon then elaborates on earlier ideas with a long lament followed by high notes played on the right side of the piano–not a simple task using the pianist’s left hand. A comical muted trombone essay on the theme is followed by the trumpets and a county fair of energy and color. After things calm down, the piano quietly rolls out arpeggios, and the earlier sad bassoon theme returns. In the process the piano plays two roles until it is left alone to roll out lines from earlier passages that now seem almost improvised. The orchestra returns, sometimes with shrieks, before the trumpets demand and eventually get a halt to the proceedings.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra. He is a former member of Bay Colony Brass (where he was also the Operations/Personnel Manager), the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony, as well as trombonist and orchestra manager of Lowell House Opera, Commonwealth Opera, and MetroWest Opera. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. His fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

Read about Mussorgskyy

|