SHOSTAKOVICH, BORODIN, & TCHAIKOVSKY

Notes on the composer and the pieces

Dmitri Shostakovich

Festive Overture

Alexander Borodin

Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor

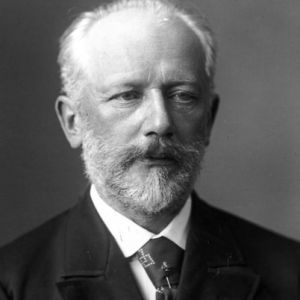

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No. 5

Return to Home Page |

Piotr Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 in E minor, op. 64, TH 29

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) was Russia’s first truly professional composer and the first to achieve fame outside Russia. He also provided the link between the Russian school and the Austro-German tradition, paving the way for Glazunov, Miaskovsky, Taneyev, Kallinikov, and others.

Tchaikovsky wrote his first song at age four and took piano lessons at five. His parents supported his musical interests, but poor employment prospects convinced them to send him instead to the School of Jurisprudence in St. Petersburg. His mother accompanied him to the capital, where they saw Glinka’s Life for the Tsar, which made a strong impression on the boy. (Life was the basis of Russian nativist operas and the first Russian opera to enter the international repertoire.) Tchaikovsky was a sensitive boy, and his mother’s leaving him alone in St. Petersburg was traumatizing; her death four years later devastated him. Nevertheless, he attended to his studies, while music provided a social life through playing, piano lessons, the opera, and composing.

After graduating in 1858, Tchaikovsky worked as a civil servant. He also studied theory with Nikolai Zaremba and piano and composition with Anton Rubinstein at the Russian Musical Society (RMS) prior to enrolling at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. After graduation, he taught at the RMS in Moscow, later the Moscow Conservatory. In 1867, he established ties with the “Mighty Five” composers. His Symphony No. 1 was performed successfully in 1868, though he suffered a nervous breakdown revising it (1874). His breakthrough work was Romeo and Juliet (1870, rev. 1880), which, along with Symphony No. 2 (1872), impressed the Five. Three string quartets followed between 1871 and 1875, along with Tempest, three operas, another symphony, Piano Concerto No. 1, and Swan Lake.

In 1876, Nadezhda von Meck, a wealthy widow and supporter of the arts, heard some of Tchaikovsky’s music and began a fourteen-year relationship with him entirely through letters. The next year, he finished Variations on a Rococo Theme, and entered a marriage whose difficulties caused him to flee to Switzerland and Italy. While abroad, he finished Eugene Onegin, the Fourth Symphony, and the Violin Concerto. He returned to Moscow to finish his teaching, but his failed marriage drove him to further travels. 1812 Overture commemorated Alexander II’s 25th anniversary as Tsar (1880) and was followed by Serenade for Strings and Maid of Orleans (1881). The Tsar ordered a staging of Eugene Onegin and later awarded Tchaikovsky a lifetime pension and the Order of St. Vladimir. The composer also became associated with the Belyayev Circle, a successor to the Five but more tolerant of Western practices. Manfred appeared in 1885.

In 1887, Tchaikovsky went on a conducting tour of Europe. His own works were well received, and he returned home eager to begin his fifth symphony. He found the project difficult, torn at the time by his craving for fame and fear of his life being exposed to the public. (Some of that probably had to do with struggling with his homosexuality.) He also worried that he was “played out as a composer.” Eventually, he began work by devising a program for his symphony, which, like the Fourth, would be based on Fate. To von Meck, he wrote: “The germ is in the introduction. The theme is Fate...a power which constantly hangs over us...and ceaselessly poisons the soul. The power is overwhelming and invincible. Nothing remains but to submit and lament in vain...is it not better to turn away from reality and lull oneself in dreams?” Fate in the Fourth was something to resist. In the Fifth, it was something to surrender to.

The Fifth Symphony’s unique structure is tied together with a “Fate” motto (possibly drawn from Life for the Tsar) that appears in each movement. The slow introduction is mournful, with the motto stated by the clarinet. The ensuing Allegro rolls out a dotted triple rhythm and builds to a stormy passage and then a romantic theme. After a horn cadence, the development builds with “alert” calls in the winds that reappear in transitions. From there, the music varies from balletic to stormy. After a climax, the motto returns in the bassoon and works through the orchestra in a long multifaceted recapitulation. The gloomy ending fades darkly into the string basses and timpani.

The Andante is music of sadness, exhilaration, and depression. It begins with a series of chords, as if the subject of the first movement has only partially recovered from the gloom. A famous horn solo creates a romantic and sentimental mood until the oboe chimes in to brighten the atmosphere. The strings then take up the main melody with commentary from soloists. After a climax, the music settles back in resignation, but agitation returns, memories darken, and Fate storms forth from the brass. Passion reaches new heights, but Fate thunders forth in the trombones. All is spent, and the music dies down, exhausted.

The Scherzo begins as a melancholy waltz, based on a street song Pimpinella that Tchaikovsky heard in Italy. A real “scherzo” takes over as the orchestra flits from section to section. The waltz returns in the winds, lightening the mood. A good-natured coda begins, but Fate returns in the winds like a ghost, finally to be silenced by the brass.

The festive Finale begins with Fate in the strings, but less gloomy than before. After a somber brass chorale, it returns, now hopeful, and the trumpets reinforce it imperiously in triumph. The horns echo it but more seriously, and the orchestra launches a furious, defiant allegro. Fate sounds in the brass, as the orchestra continues its parade. After interludes of uncertainty, the orchestra storms back and exits in triumph.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is the Operations/Personnel Manager). He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. His latest fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

Return to Home Page

|