STANFORD & BEACH

Notes on the composers and the pieces

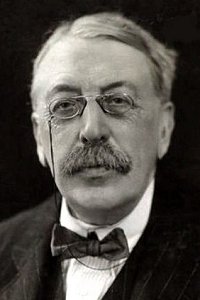

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford

Phaudhrig Crohoore

Amy Beach

Symphony in E Minor (“Gaelic”)

Return to Home Page |

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford:

Phaudhrig Crohoore, ballad for chorus and orchestra (1896)

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) was born in Dublin into a musical household that he called a “centre of real music,” where the immensely talented boy learned piano, organ, musicology and the classics. Later, he became a classics major with an organ scholarship at Queens’ College, Cambridge. He was also assistant conductor at the Cambridge University Musical Society until 1893, though as a student he moved on to Trinity College, Cambridge where he was organist from 1874 to 1892. His contributions to ensemble development in both positions, including insisting on adding women to the Trinity choir, were exemplary.

During the summers of 1874-75, Stanford went to Germany for what turned out to be unproductive composition lessons with Carl Reinecke, and in 1876 for more fruitful teaching from Friedrich Kiel. Stanford’s output during this time included his First Symphony (of seven) the oratorio The Resurrection, and ?The Veiled Prophet, the first of ten operas. He also became a professor of music at Cambridge University. In 1883, George Grove (publisher of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians) founded the Royal College of Music (RCM) in an effort to raise the standards of Britain’s orchestra players. Stanford became a professor of composition there, conducted the orchestra, and established a thriving opera department. When his friend Hubert Parry succeeded Grove as head of RCM in 1895, Stanford endorsed the appointment but chafed under Parry’s administration. (They were somewhat friendly rivals.) Among other affiliations, he took over the London Bach Choir in 1885, the Leeds Philharmonic in 1897, and a year later replaced Arthur Sullivan as conductor of the Leeds Music Festival, for which he wrote some of his best known pieces: Songs of the Sea, Stabat Mater, and Songs of the Fleet.

Charles Stanford, Hubert Parry, and Alexander Mackenzie, the best English composers since Henry Purcell (1659-1695), made up the English Musical Renaissance. Stanford’s output covered all musical forms. His instrumental music is vigorous, tuneful, and very enjoyable, but he is best known for his wonderful choral works for the Anglican Church. He longed to be a great opera composer—some of his operas were popular in their day—but none endured, though a recording of The Travelling Companion is expected this year. His well crafted and surprisingly good-natured music combines the Irish folk element, the English love for melody, and strong bass lines. Stanford adored Brahms (abetted by his contact with Brahms’s friend, violinist Joseph Joachim), but the strongest German influences on his music were Schumann and Mendelssohn. (Parry’s music sounds more Brahmsian but is nobly British at the same time.)

Stanford was popular for years, but his fortunes wavered around 1890, when his music started to seem old fashioned and, given that he was living in England, perhaps too heavily Irish in tone. (Stanford was always walking a line between his Irish heritage and his English home.) Many found Stanford’s music lacking emotion. Ralph Vaughan Williams considered his former teacher “in the best sense of the word Victorian…the musical counterpart of the art of Tennyson, Watts, and Matthew Arnold.” George Bernard Shaw, whose negative reviews hurt Stanford with the English public, described him as a struggle between “the Celt and the Professor” with too much Professor. Things got worse when Edward Elgar burst onto the scene in 1899 with Enigma Variations, and Richard Strauss, a friend of Elgar’s but abhorred by Stanford, referred to Elgar as England’s first progressive composer (probably correctly). The Great War took several of his friends and former pupils, and Parry’s death in 1918 was another blow. Still, he soldiered on and completed his last symphonies and the six Irish Rhapsodies, though in his last years, he openly lamented modern musical tendencies.

As fine as his music was, Charles Stanford’s greatest legacy was the traditions he maintained in Cambridge, his sublime music for the Anglican church, the treasure trove of composers he taught, and the music they wrote. As a teacher, he was strict, highly critical, often blunt, and sometimes cruel—his “Damned ugly m’boy!” at the sight of a plethora of notes on a score froze many a student—but he could be kind, too. Stanford was a rebel from his student days, and his strictness drove many students to rebel against him in a way that helped them become among the finest English composers of the Twentieth Century. Many credited him for much of their success. His students included Edgar Bainton, Arthur Benjamin, Arthur Bliss, Rutland Boughton, Frank Bridge, George Butterworth, Rebecca Clarke, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Walford Davies, Thomas Dunhill, George Dyson, Eugene Goossens, Ivor Gurney, Leslie Heward, Gustav Holst, Herbert Howells, William Hurlstone, John Ireland, Gordon Jacob, Ernest John Moeran, Arthur Somervell, and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Holst put it best on the day Stanford died when he told Herbert Howells: “The one man who could get any one of us out of a technical mess is now gone from us.”

Phaudhrig Crohoore (1896) is an Irish ballad for chorus and orchestra that probably sprung from Stanford’s successful opera Shamus O’Brien. It was one of several efforts to create another winning choral ballad after an earlier ballad, The Revenge. The text is the eponymous poem by Sheridan Le Fanu about a “bold, rough-hewn Irishman with a heart of gold, against a backdrop of family feuding and romance” (Christopher Howell). The work hit a snag when Halle choristers found, “For he was the devil…He could get round her” obscene and refused to sing it. Stanford argued that, “The poem is recited even by parsons at penny church readings” and refused to change the text. For a while, it appeared that his publisher would not allow the passage, but the work was published as written. Stanford’s music captures the rogue Irish spirit in a bardic, folkish manner, full of muscular strong-downbeat triple rhythms, reflective, wistful sections, jigs, and a magical ending that wistfully reflects on events. Very effective is the way Stanford treats the separate vocal choirs like soloists conversing with each other.

Phaudhrig Crohoore (Patrick Connor)

from The Poems of Le Fanu (1896)

Poem by J. Sheridan Le Fanu

Oh! Phaudhrig Crohoore was the broth of a boy,

And he stood six foot eight,

And his arm was as round as another man’s thigh,

’Tis Phaudhrig was great,—

And his hair was as black as the shadows of night,

And hung over the scars left by many a fight;

And his voice like the thunder was deep, strong, and loud,

And his eye like the lightnin’, from under the cloud.

And all the girls liked him for he could spake civil,

And sweet when he chose it, for he was the divil.

An’ there wasn’t a girl from thirty five undher,

Divil a matter how crass but he could come round her,

But of all the sweet girls that smiled on him, but one

Was the girl of his heart, an’ he loved her alone.

An’ warm as the sun, as the rock firm an’ sure

Was the love of the heart of Phaudhrig Crohoore,

An’ he’d die for one smile from his Kathleen O’Brien,

For his love, like his hatred, was sthrong as the lion.

But Michael O’Hanlon loved Kathleen as well

As he hated Crohoore, an’ that same was like hell.

But O’Brien liked him, for they were the same parties,

The O’Briens, O’Hanlons, an’ Murphys, and Cartys—

An’ they all went together an’ hated Crohoore,

For it’s many’s the batin’ he gave them before—

An’ O’Hanlon made up to O’Brien an’ says he,

I’ll marry your daughter, if you’ll give her to me,—

And the match was made up, an’ when Shrovetide came on,

The company assimbled three hundred if one,—

There was all the O’Hanlons, an’ Murphys, an’ Cartys,

An’ the young boys an’ girls av all o’ them parties.

An’ the O’Briens av coorse, gothered strong on that day

An’ the pipers an’ fiddlers were tearin’ away,

There was roarin’, an’ jumpin’, an’ jiggin’, an’ flingin’,

An’ jokin’, an’ blessin’, an’ kissin, an’ singin’,

An’ they wor all laughin’, why not to be sure,

How O’Hanlon came inside of Phaudhrig Crohoore,

An’ they all talked an’ laughed the length of the table

Atin’ an’ dhrinkin’ all while they wor able,

And with pipin’ an’ fiddlin’ an’ roarin’ like tundher,

Your head you’d think fairly was splittin’ asundher;

And the priest called out “silence ye blackguards agin,”

An’ he took up his prayer-book, just goin’ to begin,

An’ they all held their tongues from their funnin’ and bawlin’

So silent you’d notice the smallest pin fallin’;

An’ the priest was just beginin’ to read, whin the door

Sprung back to the wall, and in walked Crohoore,

Oh! Phaudhrig Crohoore was the broth of a boy,

An’ he stood six foot eight,

An’ his arm was as round as another man's thigh,

’Tis Phaudhrig was great,—

An’ he walked slowly up, watched by many a bright eye,

As a black cloud moves on through the stars of the sky,

An’ none sthrove to stop him, for Phaudhrig was great,—

Till he stood all alone, just apposit the sate,

Where O’Hanlon and Kathleen, his beautiful bride,

Were sitting so illigant out side by side,—

An’ he gave her one look that her heart almost broke,

An’ he turned to O’Brien her father and spoke,

An’ his voice, like the thunder, was deep, sthrong, an’ loud

An’ his eye shone like lightnin’ from under the cloud,

“I didn’t come here like a tame, crawlin’ mouse,

But I stand like a man in my inimy’s house,

In the field, on the road, Phaudhrig never knew fear,

Of his foemen, an’ God knows he scorns it here;

So lave me at aise, for three minutes or four,

To spake to the girl I’ll never see more.”

An’ to Kathleen he turned, and his voice changed its tone,

For he thought of the days, when he called her his own,

An’ his eye blazed like lightnin’ from undher the cloud

On his false-hearted girl, reproachful and proud,

An’, says he, “Kathleen bawn is it thrue what I hear

That you marry of your free choice without threat or fear,

If so spake the word an’ I’ll turn and depart,

Chated once and once only by woman's false heart.”

Oh! sorrow and love made the poor girl dumb,

An’ she thried hard to spake, but the words wouldn’t come,

For the sound of his voice, as he stood there fornint her,

Wint could on her heart as the night wind in winther.

An’ the tears in her blue eyes stood tremblin’ to flow,

And pale was her cheek, as the moonshine on snow;

Then the heart of bould Phaudrig swelled high in its place,

For he knew, by one look in that beautiful face,

That though sthrangers an’ foemen their pledged hands might sever,

Her true heart was his and his only for ever.

An’ he lifted his voice like the agle’s hoarse call,

An’ says Phaudhrig, “She’s mine still, in spite of ye all.”

Then up jumped O’Hanlon, an’ a tall boy was he,

An’ he looked on bould Phaudhrig as fierce as could be,

An’ says he, “by the hokey, before you go out,

Bould Phaudhrig Crohoore, you must fight for a bout.”

Then Phaudhrig made answer, “I’ll do my endeavour,”

An’ with one blow, he stretched bould O’Hanlon for ever.

In his arms he took Kathleen, an’ stepped to the door;

And he leaped on his horse, and flung her before;

An’ they all were so bother’d that not a man stirred

Till the galloping hoofs on the pavement were heard.

Then up they all started like bees in the swarm,

An’ they riz a great shout, like the burst of a storm,

An’ they roared and they ran and they shouted galore;

But Kathleen and Phaudhrig they never saw more.

But them days are gone by, an’ he is no more;

An’ the green grass is growin’ o’er Phaudhrig Crohoore,

For he couldn’t be asy or quiet at all;

As he lived a brave boy, he resolved so to fall.

And he took a good pike—for Phaudhrig was great—

An’ he fought, an’ he died in the year ninety-eight.

An’ the day that Crohoore in the green field was killed,

A sthrong boy was sthretched, and a sthrong heart was stilled.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra and Bay Colony Brass (where he is the Operations/Personnel Manager). He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony, as well as trombonist and orchestra manager of Lowell House Opera, Commonwealth Opera, and MetroWest Opera. He is a regular reviewer forAmerican Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback Magazine. His fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

Return to Home Page

|