MAHLER AND STRAUSS

Notes on the composers and the pieces

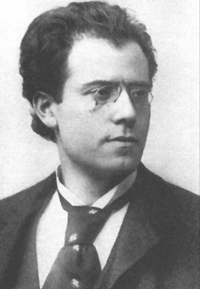

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 5

Richard Strauss

Don Juan

Return to Home Page |

Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler was born to a German-speaking, Austrian Jewish family in Kaliste, Bohemia, on July 7, 1860. The second of fourteen children, of whom six survived infancy, he showed musical talent at an early age. At fifteen he entered the Vienna Conservatory, studying piano, harmony, and composition, and three years later he enrolled in Vienna University, where he attended lectures given by Anton Bruckner. Though his first love was composing, Mahler began his career as a conductor, honing his trade in a series of opera house posts before taking up the directorship of the Vienna Opera in 1897. During this period, he composed Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer; 1883-1885), several collections of songs on texts from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Young Boy’s Magic Horn; 1887-1901), and his First (1884-1888), Second (1888-1894), and Third (1893-1896) Symphonies. He completed his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies in 1902. That same year he married the glamorous Alma Schindler, twenty years his junior.

Symphony No. 5

“The Fifth is an accursed work. No one understands it…I wish I could conduct the first performance 50 years after my death!” Mahler moaned before the work’s Cologne premiere in 1904. An earlier read-through with the Vienna Philharmonic had left him dissatisfied and Alma accusing him of writing a “symphony for percussion.” Mahler trimmed the score (whether at Alma’s behest is debatable) but not enough to stave off hostile critics. The result was five years of revising—more than required by any of his other symphonies—before the final version appeared in 1909.

Mahler explained the problem in a letter to Georg Goehler shortly before his death: “I…had to reorchestrate [the Fifth] completely. I can’t understand how I could have written so much like a beginner…The routine I had acquired in my first four symphonies simply left me in the lurch, as if a wholly new message demanded a wholly new technique.”

Mahler’s first four symphonies, the so-called Wunderhorn symphonies, were like multi-movement tone poems. They were written in a vocal style, and all but the First used voices and emphasized the woodwinds and brass. The Fifth is an abstract instrumental work that gives more to the strings and uses no voices. More than his earlier works, its adherence to form is tight, complex, and innovative. The Fifth’s unusual development features ideas which undergo constant evolution without repetition, evolution both within a given movement and from movement to movement. The symphony is full of polyphony and counterpoint, particularly in the third and fifth movements, perhaps reflecting Mahler’s immersion in Bach during the symphony’s composition. Here Mahler uses a progressive tonality, changing keys freely, without adhering to classical harmonic relationships. These qualities demanded far more clarity of textures and orchestral balances than anything else Mahler had written previously.

The symphony is arranged in three parts. Part I includes the thematically related first two movements. Part II is the Scherzo. Part III comprises the last two movements, also thematically related. Mahler was moving away from programmatic composing by the Fifth, but an apparent theme of per aspera ad astra (through difficulties to the stars) suggests he had not entirely abandoned extramusical ideas.

1) Trauermarsch. (Funeral March.) Mahler was fascinated by marches, particularly funeral marches, so it is no surprise that he turned one into a symphonic movement. The opening fanfare, inspired by bugle calls the composer heard in his youth from a nearby military base, is followed by two march episodes, two “trios,” and a coda. Each section is introduced by a brief variant of the fanfare, three from the trumpet and a ghostly one played by the timpani. The first march combines a stately tune related to Mahler’s song Der Tambourg’sell (about a deserter marched to his execution), heavy statements based on the fanfare triplets, and some heroic striving from the trumpet. Trio I lashes furiously, surging with grief and rage. The second march section is more dotted in rhythm and sterner in nature, while Trio II is sweet and consoling. The movement ends with the coda fading into the distance before disappearing abruptly with a pizzicato in the low strings.

2) Stürmisch bewegt. Mit größter Vehemenz. (Tempestuously. With the greatest vehemence.) Mahler considered this the real first movement, and like many symphonic first movements, it is in sonata form. Short, gruff figures in the low strings and barking trombones introduce the opening theme in the first violins, a sharply rising interval and a set of short furious runs, driven hard, impetuously, and hurriedly from the upbeat. The music swirls and rages in a nightmarish hell, with, as Constantine Floros describes, descending tritones (known as the devil in music) and chromatic woodwind runs denoting the Inferno. On two occasions, the low brass drive everything into the ground, one time furiously, the other heavily. The only repose comes in a variation of the second trio of the Trauermarsch and a long lament in the cellos. Optimism is limited to a cheeky march and a failed attempt at a brass chorale before the fury peters out with a sigh and a murmur.

3) Scherzo. Kräftig, nicht zu schnell (Vigorously, not too fast). This is the longest movement and was the first to be completed, albeit with great difficulty. After a funeral march and a struggle in Purgatory, we are now in a movement where, in the composer’s words, “There is nothing romantic or mystical…only an expression of extraordinary strength. It is mankind in the full brightness of day, at the zenith of life…Each note…is profoundly alive, and the whole thing spins like a whirlwind or a comet’s tail.” Biographer Henry-Louis de La Grange calls it one of Mahler’s few movements with “no element that could be interpreted as ironic or parodic.” The solo “obbligato” horn dominates the proceedings, calling out boldly and confidently. The complex structure combines scherzo elements with sonata form and adds a fugato. What come through most clearly are the twistings, turnings, and revelries of an Austrian Ländler and a sweet little waltz, creating moods that range from ebullient to pleasantly wistful. The music plays all kinds of tricks with the rhythm, often turning the ONE-two-three on its head. It pauses only for a breath-catching dialogue between two horns. Things really let loose in a wild development and more so in a mad stretto that ends the movement with dazzling, perhaps drunken joy.

4) Adagietto. Sehr langsam (Very slow.) This period of repose for strings and harp is a song without words. The conductor Willem Mengelberg claimed that Gustav and Alma told him it was a love song to Alma, and Floros points out a passage in the middle that resembles the “gaze motif” in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. La Grange cautions that “Alma who…took pride…in the declarations of love…from the four great men in her life, never mentioned the Adagietto among them.”

5) Rondo-Finale: Allegro giocoso. Frisch. (Fast, playful, fresh). The finale is a complex blend of sonata, rondo, and fugue. A sustained A in the horn magically wakes up the orchestra, and solo winds introduce many of the ideas for this movement, some from earlier in the symphony. The horns sail into the rondo theme, and after the first of three lively fugues, we’re off. The music flies by, some of it lyrical, some vigorous. Tonality remains progressive but always in upbeat major keys. At the beginning of the third development, the finale’s only contemplative passage takes one last look backward. At the end, everything picks up in speed, spirit, and boisterousness, culminating in a triumphant chorale and a rush to the finish.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, Dudley House Orchestra, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is also the Operations/Personnel Manager), and is a local freelancer. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener's Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony.

Read about Strauss

Return to Home Page

BUY TICKETS

|