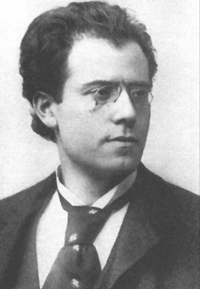

MAHLER

Program Notes

Return to Home Page |

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 9

Gustav Mahler was born in 1860 to a German-speaking, Austrian Jewish family in Bohemia. As a young boy, he took piano lessons and absorbed the sounds of parades and a nearby military base that he often imitated in his symphonies. As a teenager, he moved to Vienna to study harmony with Robert Fuchs and composition with Franz Krenn. Although Mahler is now known mainly as a great composer, he was also a fine conductor, a skill he honed the same way many great conductors did in the early twentieth century: by conducting opera. After leading performances in Prague, Leipzig, Budapest, and Hamburg, he took over the prestigious Vienna Court Opera in 1897, where his stewardship produced a golden era for the company.

Misfortune started to plague Mahler’s life in 1901 when he nearly died from bleeding hemorrhoids. In 1902 he married the 20 years younger Alma Schindler. Two daughters, Anna and Maria, followed during one of the happiest periods of his life, but that spell was broken in 1907. His four-year-old daughter Maria (nicknamed Putzi) died of scarlet fever or diphtheria, traumatizing her father to the point where he could not bear the mention of her name.1 At the same time, Mahler’s heart problems were discovered, and his doctor ordered him to exchange his beloved long walks in the woods and mountains for a more sedentary life. A displeased Mahler wrote Bruno Walter: “The solitude…makes me feel all the more distinctly that everything is not right with me physically. Perhaps indeed I am being too gloomy…but…I have been feeling worse than I did in town, where all the distractions helped to take my mind off things.” Painful mental links between Maria’s death and the family’s summer residence then drove him to move to Toblach in the mountainous Tyrol region on the Austro-Italian border. In the fall of 1907, the onslaught of anti-Semitic attacks from the press and within the Opera2 (despite his converting from Judaism to Catholicism just prior to accepting the appointment) drove him to flee Vienna for New York City, where he conducted the Metropolitan Opera and took on the music directorship of the New York Philharmonic. Any happiness gleaned during that period dissipated in 1911 when he learned that his wife had an affair with architect Walter Gropius, and he developed heart problems from bacterial endocarditis. After the treatment he sought in Europe failed, he returned to Vienna, where he succumbed to heart failure in May 1911.

Although Mahler’s conducting chores at the Vienna Court Opera limited his time for composing to summers, he still managed to produce a powerful catalog of works. The earliest was the Piano Quintet (1876). From there he wrote several pieces that featured the voice: the cantata Das klagende Lied (1880), Drei Lieder for tenor and piano (1880), Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer, 1885), and Ruckert-Lieder (1902) . In 1889, he wrote his Symphony No. 1 “Titan,”3 only for it to be met with critical disapproval. His second, “Resurrection” (1894), was better received. The gigantic No. 3 from 1896 (one of the longest symphonies, if not the longest in the standard repertoire) earned the greatest acclaim yet for a Mahler work. The Haydnesque No. 4 (1900), the first to be composed in his bare-bones summer cabin in the Austrian village of Maiernigg, also impressed audiences. No. 5, arguably Mahler’s happiest symphony, was composed during one of his happiest periods. He began it in the summer of 1901 after meeting Alma Schindler in 1900. He married her in March 1902 and finished the work that summer. Things changed with one of his saddest works, Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children, 1904) about the deaths of children, a subject Alma found strange coming from a father of two young daughters. That same year he composed his Sixth Symphony (“Tragic”), his first that did not end in triumph or positive transformation. Conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler called it the “first nihilist piece in the history of music.” Next came the most oblique and difficult of his symphonies, the Seventh (“Song of the Night”), which he finished in 1905. The Eighth (“Symphony of a Thousand,” 1906) was to be his grand finale, and he scored it that way with 858 singers, 171 instrumentalists, and eight vocal soloists. He did not intend to write another symphony partly because he did not want to join Beethoven and Bruckner in dying soon after (Beethoven) or before (Bruckner) finishing a ninth symphony. However, after the move to the Tyrol region, he composed Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth, 1908) and a year later, Symphony No. 9. Not long after completing it, he began a Tenth Symphony but did not live long enough to finish it.4

Mahler’s obsession with death played itself out in the Ninth Symphony, which proved to be one of his finest. The work’s four-movement structure is unusual for a symphony: two slow outer movements that can be heard almost as tone poems and two faster inner ones.

Movement 1, “Andante comodo” (comfortably slowish) combines the structures of the sonata and rondo, the latter because of frequent references of the main theme. Composer Alban Berg called this movement the

greatest Mahler ever composed. It is the expression of a tremendous love for this earth, the longing to live on it peacefully and to enjoy nature to its deepest depths before death comes… [It] is dominated by the presentiment of death…the culmination of everything on earth and in dreams, with ever more intense eruptions following the most gentle passages… [It] is strongest in the horrible moment where death becomes a certainty, where, in the middle of the deepest, most poignant longing for life, death makes itself known “with the greatest violence.”

The movement opens with a halting signature rhythm followed by a weary-sounding dropping major second that suggests the words Leb’ wohl! (“Farewell,” as noted by Mahler in his score). The second violins then play a hopeful, wistful theme. Those two ideas and the opening rhythmic figure dominate this movement. The horns submit their idea on the main theme, and the full string section takes over. Much of this music suggests a processional creating the image of walking and searching. After the first of several fanfares, climaxes ensue like rushes up to a summit. The last one, set in the halting rhythm from the opening, is positively frightening. Along the way are heard dark, chordal passages in the middle and low brass that scholars interpret as death strokes. The rest of this movement’s half-hour works with these materials. Many Mahlerians hear this movement as a portrait of Mahler struggling with the idea of dying, but it is also easy to hear it as an exploration of life.

Movement 2. Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers. Etwas täppisch und sehr derb (At the pace of a leisurely Ländler. Rather clumsy and very rough) seems to examine Mahler’s feelings of youth and energy, employing one of his favorite musical forms, the Ländler, an Austrian folk dance whose earthy character—a product of its slow triple rhythm and strong emphasis on downbeats—resonated with Mahler’s love of nature and the rustic outdoors. The Ländler alternates with faster, increasingly reckless sections that maintain their link to the waltz passages by maintaining the movement’s strong 3/4 meter. There is also a slower lyrical section that reflects on the dropping second from the first movement. For its final section, Mahler scores the Ländler transparently with solos for the horns, several winds, and the violas. It ends with the Ländler motif played by the piccolo and underscored by the contrabassoon and pizzicato violins and violas.

Movement 3. Rondo-Burleske Allegro assai. Sehr trotzig (very defiant) ratchets up the tension to near violence as the fleeting darkness that haunted the Ländler is given free rein with blistering intensity, anger, and madness. Mahler was often accused of being unable to write counterpoint, but he indulges in that form with a folklike earthiness here. There are beautiful passages though, particularly the short brass chorale toward the end decorated with sweet Mahlerian trumpet solos before madness returns. Worth notice are the melodic turns that dominate this section and much of the finale.

Movement 4. Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend (very slowly and cautiously) sounds like a companion to the first movement, exemplifying the sharp temperamental differences between the outer, energetic movements and the quieter inner ones. Both outer movements rely heavily on warm string textures and heroic French horns. Woodwinds comment and rhapsodize, trumpets display anger and sometimes even panic, the low brass project an aura of doom, and the underlying timpani suggest a muscular uneasiness. This is music of concession and even welcome, as opposed to the exploring nature of the first movement, the youthful sarcasm of the second, and the lashing out of the third. The exquisite ending quotes a touch of the fourth song of Kindertotenlieder: “…in the sunshine! The day is fair on those hills in the distance.” Bruno Walter described this movement as “a peaceful farewell; with the conclusion, the clouds dissolve in the blue of heaven.”

Mahler’s fears prior to composing the Ninth came to pass when he died in May 1911 before he could conduct the symphony or hear it performed. Bruno Walter, who would be a major Mahler interpreter, led the Vienna Philharmonic in the symphony’s premiere in June 1912.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is the Operations/Personnel Manager). He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. His latest fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

_____

1 Her sister, Anna, went on to be a successful sculptor.

2 Some of the hostility encountered at the Opera was due to frequent absences for conducting appearances outside of Vienna.

3 Mahler often spoke of his disdain for nicknames. Several of his symphonies have them, but as far as I can tell, he was responsible only for “Resurrection.”

4 He completed only the first movement and a “short score” of four others. Several composers, most prominently Deryck Cooke, produced completions of the Tenth that have been performed and recorded in recent years.

Return to Home Page

|