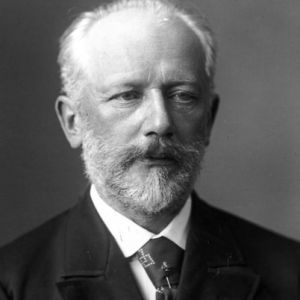

TCHAIKOVSKY

Notes on the composers and the pieces

Sergei Prokofiev

Symphony No. 1 “Classical”

Saint-Saëns

Piano Concerto No. 2

Return to Home Page |

Piotr Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 “Pathétique”

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) was born in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia. He learned German and French early in life from his governess, Fanny Durbach, wrote a song at age four, and began piano lessons at five. His parents supported his musical interests, but poor employment prospects convinced them to send him 800 miles to the School of Jurisprudence in St. Petersburg. His mother accompanied him to the capital, where they saw Glinka’s Life of the Tsar, which made a deep and lasting impression on him. Tchaikovsky was a sensitive boy, and his mother’s leaving him alone in St. Petersburg was traumatizing; her death four years later devastated him. Nevertheless, he attended to his studies, while music provided a social life through playing, piano lessons, the opera, and composing.

After graduating in 1858, Tchaikovsky worked as a civil servant. At the same time, he studied theory with Nikolai Zaremba and piano and composition with Anton Rubinstein at the Russian Musical Society (RMS) prior to enrolling at the St. Petersburg Conservatory when it opened in 1862. After graduation, he taught for Nicolai Rubinstein at the RMS in Moscow, later the Moscow Conservatory. In 1867, he established ties with Mily Balikirev, leader of the Five, a group of nativist composers that included Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Modest Mussorgsky, César Cui, and Alexander Borodin. His First Symphony was premiered successfully in 1868, though he suffered a nervous breakdown while revising it (1874). Nikolai Rubinstein’s encouragement led to his first major work, Romeo and Juliet (1870, rev. 1880). That work and his Second Symphony (1872) impressed the Five—no small accomplishment. Three string quartets followed between 1871 and 1875, along with Tempest, three operas, another symphony, Piano Concerto No. 1, and Swan Lake.

In 1876 he visited Paris and Bayreuth, where he met Liszt but was avoided by Wagner. The next year, he finished Variations on a Rococo Theme, and entered a marriage whose later failure caused him to flee to Switzerland and Italy. While abroad, he finished Eugene Onegin, the Fourth Symphony, and the Violin Concerto. He returned to Moscow to finish his teaching, but continued marital difficulties drove him to further travels.

1812 Overture commemorated Alexander II’s 25th anniversary as Tsar (1880) and was followed by Serenade for Strings and Maid of Orleans (1881), his first opera produced outside of Russia. The Tsar ordered a staging of Eugene Onegin and laterawarded Tchaikovsky a lifetime pension and the Order of St. Vladimir. The composer also became associated with the Belyayev Circle, a successor group to the Five which was more tolerant of Western practices.

Among Tchaikovsky’s late works were Manfred (1885), Symphony No. 5 (1888), Hamlet and Sleeping Beauty (1889), Queen of Spades and Souvenir de Florence (1890) and Nutcracker (1892). He conducted the premiere of his last work, the Sixth Symphony, on October 28, 1893. Nine days later he was dead at age 53.

Tchaikovsky was homosexual, but scholars disagree as to how comfortable he was with his sexual orientation. He kept this side of his life private, while enjoying support from family and friends, particularly his brother, Modest, also a homosexual. Some inner turmoil was revealed in works like Francesca da Rimini, Symphony No. 4, and Eugene Onegin (particularly the “letter aria”). Debate persists as to whether he died from drinking contaminated water in a cholera epidemic or committed suicide out of fear that his homosexuality might become known.

At the same itme, Tchaikovsky was strongly affected by the women in his life, beyond the earliest influences of his mother and Durbach. An engagement to a Belgian soprano, Désirée Artôt, fizzled without serious consequences when she married a Spanish baritone. Antonina Miliukova, an unbalanced former student, was another matter. Tchaikovsky received a love letter from her in 1877 while he was working on Eugene Onegin. Her attentions (including a suicide threat) and perhaps a hope that marriage would hide his homosexuality, led the composer into the disastrous union that he abandoned after less than three months. The two were never divorced, but he was beset with rancor and fear that Antonina would expose his homosexuality.

Nadezhda von Meck was a wealthy widow and supporter of the arts with whom Tchaikovsky maintained a fourteen-year relationship entirely through letters. She was a source of comfort during his marriage crisis and even tried to pay off Miliukova. For thirteen years, she paid him a yearly stipend that she stopped in 1890, claiming financial problems. Her real reasons were more serious and personal, possibly including worry that her family would expose Tchaikovsky’s homosexuality. Tchaikovsky did not depend on her financial assistance by then, but he was so hurt that he ended the friendship without learning the truth, to the eternal distress of both of them.

Piotr Tchaikovsky was arguably the first truly professional composer from Russia, as well as the first to achieve substantial fame outside Russia. He also provided the link between the Russian school and the Austro-German tradition, paving the way for Glazunov, Miaskovsky, Taneyev, Kallinikov, and others.

When Tchaikovsky began his Sixth Symphony in earnest in 1893, recent performances of Nutcracker and Iolanta had not gone well and he was still reeling from the collapse of his friendship with von Meck, and a previous attempt at a sixth symphony had produced only drafts. Work went quickly, though it was interrupted by a tour, and orchestration proved daunting. The result was the composer’s “most sincere” work, something he put his “whole soul” into. He intended to title it Program Symphony (No. 6), but the prospect of being questioned about a program he did not want to divulge derailed that title in favor of Modest’s suggested patetichesky (pathetic, i.e., passionate suffering or emotional, as opposed to the English pitying). Tchaikovsky wanted to withdraw that, too, but his death left his publisher free to use Pathétique, not surprising in a country enamored of French culture. All that said, there are those who hear the Pathétique as autobiographical, a symphonic suicide note, or a poem of impending death. The premiering orchestra’s doubts about its worth affected Tchaikovsky’s conducting, leaving the audience bewildered, as well. The second performance, at a memorial service, was overwhelmingly positively received.

Like all Tchaikovsky’s symphonies, Pathétique is imbued with the deft touch of a master ballet composer.

I. Adagio—Allegro non troppo is in quasi-sonata form. It opens slowly with a bassoon searching about a bed of basses as it states the first theme with violas added on cadences. The violins enter with a more darting version of the first theme, which begins as balletic but soon becomes more militant with the fanfaric entry of the brass. After a pause, the second theme, based on Don José’s ’Flower Song” from Carmen (which Tchaikovsky adored) sweeps forward in the violins. Interspersed is commentary from the woodwinds plus a smooth line in the brass. The relatively short Allegro non troppo development is triggered by a startling accent. It expands into conflict based mostly on the first theme, with stern trumpets, chugging cellos, a chant from the Russian Orthodox Requiem in the trombones, an odd march, and a powerful calling out in the low brass. After everything settles, the rapturous second theme reappears to begin the recapitulation. The movement ends with a quiet brass and wind processional over walking low strings.

II. Allegro con grazia. This “limping waltz” resembles the waltz from the Nutcracker but is in 5/4 meter (2+3, the limp followed by the waltz). The long trio adds a touch of sadness and unease.

III. Allegro moto vivace begins lightly with Mendelssohnian gestures, but quickly bursts into a stunning march of amazing energy, swagger, and even militance, ending with a crisp flourish which is often mistaken by first-time listeners as the end of the symphony.

IV. Adagio lamentoso opens with a sigh and takes a sad look back on the second theme of the first movement. Much of the motion is downward until a new melody in the violins and later in the brass looks up hopefully—only to be struck down by a hammering climax. The hopeful theme peers out and rallies in desperation before it collapses amid snarling muted horns. Sad trombone chords sing farewell, and the symphony sinks into the despair and darkness of the basses and fades into silence.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is the Operations/Personnel Manager). He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. His latest fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

Return to Home Page

|