RIMSKY-KORSAKOV, GRIEG, & SIBELIUS

Notes on the composers and the pieces

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Russian Easter Overture

Edvard Hagerup Grieg

Piano Concerto

Return to Home Page |

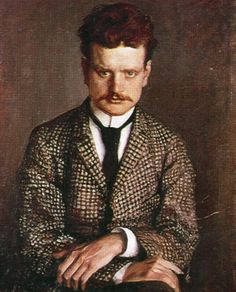

Jean Sibelius: Symphony No. 2

To write about Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) is to write about Finland’s unusual history. The country was ruled by Sweden from c.1200 until 1809 when Russia drove the Swedes out and ruled Finland as an independent Grand Duchy run by the Swedish-speaking minority. The rest of the country spoke Finnish. In 1835, the publication of the epic Kalevala stimulated interest in Finnish folklore that led to a nationalist movement in the middle of the century. As Adolf Arvidsson put it, “we are no-longer Swedes, we do not want to become Russians, let us therefore be Finns.“ It was not until 1892 that the Finnish language was granted equal status with Swedish. Russia later restricted speech and assembly in 1899 and in 1901 absorbed the Finnish army into the Russian army. Finland granted universal suffrage in 1906, but its parliament remained subject to the Tsar’s wishes. The Finns resisted all this passively but with increasing intensity. It was not until 1917 that Finland broke away from Russia. After a short, violent civil war, it became a republic in 1919.

Johan Christian Julius Sibelius (a Latinization of Sibb) was born into this environment in Hämeenlinna, 60 miles north of Helsinki. His family was Swedish speaking, and the boy, known as Janne, began his education in a Swedish school. (The name Jean was taken at age twenty.) Sibelius transferred to a Finnish school a few years later. Even so, Swedish remained his first language, and he wrote many songs in that tongue. The composer would later take up Finnish, but he was not comfortable with it until his twenties.

Sibelius envisioned a soloist career as a violinist, but stage fright and damage to his bow arm limited him to orchestra and chamber playing. He started composing in 1875, and for a long time wrote chamber music in the style of Beethoven and Haydn. In 1885, he briefly attended law school, but his true vocation began with four years of violin and composition study at the Helsinki Music Institute, where he met Italian composer Ferruccio Busoni. He also knew people in the Finnish arts, most importantly, the brothers Järnefelt: composer Armas and painter Eero.

After graduation, Sibelius went to Berlin for study with Albert Becker, though he benefitted more from his exposure to Wagner, Strauss, and most significantly, a performance of Finnish composer Robert Kajanus’s Aino Symphony based on the Kalevala. A year after returning to Finland, he went to Vienna where he studied with Karl Goldmark and Robert Fuchs. He also began his transition from German classicism to composers like Wagner and Bruckner, as well as Scandinavians and Russians, particularly Tchaikovsky.

Sibelius’s increasing interest in Finnish culture was encouraged by the Järnefelts, whose sister Aino eventually became Sibelius’s wife. The two exchanged letters, with the composer writing in Swedish and Aino in Finnish. Exposure to the Kalevala induced him to advocate for Finnish folk music and composers to the point where he and his music were rallying points for Finnish resistance to Russia. His music in support of the 1899 Press Pension Celebrations helped support the press against new Russian restrictions. One of those pieces, Finland Awakes, was later expanded into Finlandia, the musical signature of Finland.

Sibelius’s first great work was Kullervo (1891), drawn from the Kalevala. “I now grasp...purely Finnish tendencies in music less realistically but more truthfully than before,” he wrote Aino. Kullervo established Sibelius as a composer and introduced his Finnish musical voice. There followed a series of tone poems: En Saga, Swan of Tuonela—which revealed Sibelius’s true brilliance—and then Lemminkäinen Legends, Wood Nymph, King Christian II¸ and Finlandia. The dark and at times forbidding Symphony No. 1 combined the influence of Tchaikovsky and the haunting Sibelian sound of the tone poems to help set his international reputation, most importantly in Germany.

In 1900, the Sibelius family vacationed in Rapollo, Italy, where the warm, relaxed Italian atmosphere expanded the composers imagination. At first, he made plans for works based on Don Juan and Dante’s Divine Comedy, plus a set of tone poems to be called A Festival. What actually emerged were sketches for a Second Symphony that would use some of the ideas from the projected works. Completed in Finland, the symphony was “inspired by Italy and the Mediterranean...with sunshine and blue sky and jubilant happiness.” (Kajanus and conductor Georg Schnéevoigt thought it symbolized Finnish resistance to the Russians, a point rejected by the composer.) The Second Symphony is more optimistic and refined than the First. Its scoring is lighter, and its tone leans more toward Beethoven than Tchaikovsky. It was the last of Sibelius’s Romantic symphonies. The Sibelius of the future was a more refined, reserved, and less overtly emotional composer.

Symphony No. 2. Allegretto. Sibelius’s novel treatment of sonata form works with groups of ideas that he assembled “as if the Almighty had thrown down pieces of a mosaic from Heaven’s floor and asked me to put them together.” The ideas have an indefinable common source and grow organically from each other. Sibelius “examines each piece in turn; in the development he organizes them into a pattern, and in the recapitulation, he sets a distinctive stamp on each of them, placing them in almost the same order…and at times simultaneously” (Erik Tawaststjerna). There are conflicting analyses of this movement, e.g., the number of groups, where the development and the recapitulation begin. It all flows so naturally that it is possible to pick out the germs and keep track of them: the opening repeated-note figure followed by a related passage in the winds; French horn chorales; a rising ladder-like figure in the bassoons; a recitative passage in the violins; a long swelling note in the strings followed by a downward flourish, an idea that appears throughout the work. The development (probably beginning with the oboe playing that last motif) brings ideas together in two layered and sustained climactic waves, a smaller one then a much larger one, before the recapitulation (possibly after the last brass climax) allows them to separate.

Andante ma rubato. The Don Juan idea seems to appear here. As Sibelius wrote, “on Juan knew who it was. It was death.” That seems associated with the long somber melody in the bassoons after the opening walking bass pizzicato. Written in the score over the ethereal string theme is “Christus,” perhaps from the Dante idea. Many observers find this movement a struggle between death and life, but it can be heard as a darker, more striving continuation of the first movement, with similar toned themes and a stern reflection of those sustained, swelling climaxes.

Vivacissimo: Lento e soave alternates two fast sections with sad trios featuring oboe solos whose repeated notes are related somewhat to the rhythm that opens the work. In the second fast section, a horn passage presages the main motif of the Finale. Sibelius then draws from Beethoven’s Fifth to build a bridge passage to the Finale, though he does so more portentously with marked hints as to what is to come.

The heroic Finale, in standard sonata form, proceeds continuously from the third movement with a glorious D Major motif (a rising D, E, F-Sharp) that reverses both notes and direction to create the falling F-Sharp, E, and D figure that began the first woodwind tune in the opening movement. This figure creates a rapturous melody played over a driving ostinato in the trombones and then driven by syncopations in the horns. Also important is a brief fanfare figure and a string melody that obliquely suggests the symphony’s opening woodwind tune. After a theatrical bridge drawn from the string tune, scales scurry mysteriously about in the low strings under a second more somber theme that Aino Sibelius claimed honored her sister Elli, who took her own life. That second idea, stated in the oboe, begins a processional of minor key phrases with changing orchestration that continues until a modulation to the major sets off a grand fanfare. A short furtive passage in the low strings bridges to a complex development. The recapitulation begins with the first theme over the trombone ostinato, turning rapturous soon after. The earlier theatrical bridge returns now more extended, and the second theme begins another processional in the minor over the low string scales. This processional is seemingly endless as it gains power until it bursts into the major. Again the furtive bridge is heard, now in the trombones, leading to the final grand peroration led by the brass.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is the Operations/Personnel Manager). He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. His latest fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

Return to Home Page

|