MAHLER

Program Notes

Return to Home Page |

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 “Resurrection”

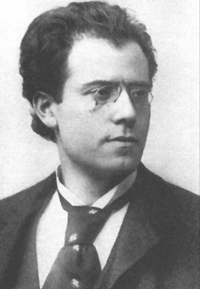

Gustav Mahler was born to a German-speaking, Austrian Jewish family in Bohemia in 1860. One of six children who survived infancy, he showed musical talent at an early age when he took piano lessons and absorbed the sounds of parades and fanfares from a nearby military base. At fifteen, he entered the Vienna Conservatory where he studied piano, harmony, and composition. Three years later he enrolled at Vienna University, where he attended lectures by Anton Bruckner. Though his first love was composing, Mahler’s main career was conducting, a trade he honed in opera houses in Prague, Leipzig, Budapest, and Hamburg. During that period, he composed Das klagende Lied (1880), Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer, 1883–1885), and his First Symphony (1884–1888).

In 1888, Mahler wrote a tone poem called Todtenfeier (Funeral Rites). Even as a 28-year-old, he was already obsessed with death and redemption. While composing the work, Mahler told his close friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner that he experienced a dream about himself, “dead, laid out in state, beneath wreaths and flowers.” (The flowers were real. They were given to him after a performance of Die drei Pintos, an opera begun by Carl Maria von Weber which Mahler completed.)

Mahler considered using Todtenfeier in a symphony, but hesitated after conductor Hans von Bülow disparaged Todtenfeier when Mahler played it for him on the piano in 1891; to von Bülow, Todtenfeier “made Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde sound like a Haydn symphony.” It was certainly not a compliment, and Mahler was devastated by this dismissal. Little more emerged from his pen until 1893. He then completed what would be the second movement of the Second Symphony and several songs that became part of a collection entitled Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Two of these songs would join the symphony, one as part of the third movement and the other as the fourth.

Mahler wanted a choral movement for the fifth and final movement, but he was inhibited from writing not only by the shadow of Beethoven’s Choral Symphony, but also by the lack of a trigger for his inspiration: a “word,” as he called it. He found that word in 1894 at von Bulow’s funeral when the choir sang Friedrich Klopstock’s Resurrection Chorale. “This hit me like lightning,” he wrote to the writer and dramatist Arthur Seidl, “and everything appeared clearly and distinctly before me!” The word was "resurrection."

The revitalized composer worked quickly, revising and expanding Todtenfeier to become the symphony’s first movement and completing the symphony in July 1894 (though he continued to revise it until 1909). To Friedrich Löhr, he wrote: “Beg to report safe delivery of a strong, healthy last movement of my Second. Father and child are both doing as well as can be expected—the latter not yet out of danger. At the baptismal ceremony, he was given the name, ‘Lux lucet in tenebris’ [The light shines in the darkness].” “[It is] the most important thing I have yet done,” he wrote to Arnold Berliner, “…a bold work, majestic in structure…the final climax is colossal…”

Mahler conducted the first three movements in Berlin in March of 1895 to a chilly reception. In December he led the complete work, again in Berlin. This time the work was more warmly received, bolstered by students with free tickets who were receptive to new music. The symphony went on to be performed more in his lifetime than any of his others. Mahler conducted it thirteen times, including at his farewell concert in Vienna after leaving the Opera.

The “Resurrection” Symhony’s nickname did not come from the composer, though the concept was on his mind when he wrote the piece, and it is the subject of its vocal texts. More complicated is the matter of the programs he reluctantly provided to “explain” his music to friends and others. Three such programs have survived. One was written at the request of King Albert of Saxony for a Dresden performance in 1901: a “crutch for a cripple,” Mahler called the program in a letter to his wife, adding that such an explanation leads to a “flattening and coarsening [whereby] the work...is utterly unrecognizable.” Later in life Mahler refused to supply these explanations. Though many scholars today believe his music preceded any program, and some add that the programs that exist should be ignored, details from these programs have influenced performances of his works.

Mahler: Symphony No. 2 “Resurrection”

I. Allegro maestoso. Mit durchaus ernstem und feierlichem Ausdruck. (With serious, solemn expression.)

Mahler told Marschalk that this movement deals with the death of the hero from his First Symphony, “whose life I catch up from a higher standpoint, in a pure mirror. He asks...why do we live and suffer...He into whose life this call has once sounded must give an answer; and this answer I give in the final movement.” For Dresden he wrote, “we are standing beside a coffin. The deceased’s battles, his sufferings and his purpose pass before the mind’s eye...[we] are gripped by a voice of awe–inspiring solemnity...What next?...What is life—and what is death? Have we any continuing existence?”

The movement is in a modified sonata form with (arguably) two expositions and two developments. It begins with a jagged outburst in the strings that reappears to start the second exposition, the second development, and the recapitulation. The first of several marches steps off in the low strings, and more themes emerge. The second appearance of the march leads to a pounding climax that suggests something ominous, but yields to the first pastoral section. The second exposition introduces more themes, including Lizst’s “symbol of the Cross” rising like a vision in the trumpets. The Cross is met by a downward motion in the horns that is transformed into a doom-laden chromatic ostinato in the basses under a funeral march.

The first development begins with more pastoral music. Other themes are treated as the music gains power and urgency. After the horns sound the Cross, the trombones take the earlier ostinato and drive it earthward in a rage, eventually to be relieved by idyllic flute and violin solos.

The second development is introduced by the jagged opening material figure and blunt percussion. Trepidatious strings are followed by a forlorn English horn tune that evolves to a march in the trumpet. A chorale based loosely on the Dies irae sounds portentously in the horns. Another march is swallowed up in a violent orchestral storm, culminating in a climax which might resemble the hammering of nails into a coffin.

The recapitulation produces some additional powerful statements from the brass and recalls the earlier pastoral music, only to return again to the doom-laden ostinato in the harp and basses. The orchestra can do nothing but tread hopelessly to its collapse into the grave.

II. Andante moderato. Sehr gemächlich. Nie eilen (Very leisurely. Never rush.)

The next two movements look back upon life, with the Andante evoking a brief gaze back on pleasant country days. Some critics believe its tone and style are out of place in the symphony. Mahler came to that view himself, conceding that he wrote it independently of the first movement and never envisioned the two going together. Claude Debussy, Gabriel Pierne, and Paul Dukas apparently agreed when they walked out of the 1910 Paris performance during this movement, much to the composer’s chagrin.

The Andante is in five parts. 1) A gentle, slightly proud Austrian Ländler. 2) A string melody (recalling the Scherzo of Beethoven’s Ninth) followed by a wistful tune in the clarinet. 3) An intimate duet between the violins’ Ländler and a cello melody interrupted by an ominous climax that darkens the mood momentarily. 4) The Ländler in pizzicato. 5) The violins sing the former cello melody, cellos and winds take up the Ländler, the two melodies come together subtly, and the movement ends gently.

III. In ruhig fließender Bewegung (With quietly flowing movement)

Here we encounter Mahler’s “confusion of life” where the “bustle of existence becomes horrible...like the swaying of dancing figures in a brightly lit ballroom, into which you look from the dark night outside. Life strikes you as meaningless.” We also encounter humor with touches of boisterousness and nostalgia before “disgust of existence in every form [culminates] in an “outburst of despair.’”

Music from the Wunderhorn song “Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt” (St. Anthony’s Sermon to the Fishes), makes up the A section of the movement and appears three times. In the song, St. Anthony, faced with an empty church, preaches to the fish (signified by the fluidity of this passage), who listen attentively before swimming off to resume their dissolute ways.

IV. Urlicht (Primeval Light). Sehr feierlich, aber schlicht (Very solemn, but simple)

This Wunderhorn song was inserted almost intact save for some enhanced orchestration. The alto pleads for a return to God who will “lighten my way up to eternal, blessed life.’ The gentle chorale in the trumpets is heard nowhere else in the symphony.

V. Finale: Im Tempo des Scherzos (In the tempo of the Scherzo)

Part 1: Wild herausfahrend (Wild and driving)

The longest movement of the symphony begins with the “cry of despair” from the third movement. Familiar earlier themes and new ones follow. After a hush, Der grosse Appell (The Grand Call) between this world and the next begins with off-stage fanfares (an idea perhaps taken from Berlioz’s Requiem). The peaceful trumpet figure returns, and trombones intone a “doom” motif. The flute and oboe play a variant of Dies irae, the solo trombone and solo trumpet reply with “resurrection,” somber pronouncements are exchanged between the orchestra and the distant brasses, and then silence.

Enter the English horn with a yearning phrase with a syncopation that creates new tension. The orchestra reacts with a fury that subsides to an almost frozen moment in time. The Dies irae re-emerges in the low brass but then expands nobly to “resurrection”—only to be stymied again when “doom” from the trombones halts the proceedings.

Suddenly, “the earth quakes” with a thunderous rumble in the percussion. The brass roar, the rest of the orchestra joins, “the graves burst open, and the dead arise and stream on in endless procession...” The Dies irae in the strings struggles with resurrection in the trumpets before emerging in cataclysmic triumph: then another silence.

A lone trombone peers out and repeats the earlier English horn motif. Off-stage “trumpets of the Apocalypse” induce a thunderous orchestral roar and shattering climax. After a pause, the skies clear, the horns sound a descending fifth, and there is angelic calm. A peaceful trumpet motif summons the horns who respond from afar with the Call. Flute and piccolo sing a long, fluttering “song of a nightingale, a last tremulous echo of earthly life!” and once again, silence.

Part 2: Auferstehn (Arise)

“A chorus of saints and heavenly beings softly breaks forth...and then appears the glory of God!” The strings join on Unsterblich leben (eternal) and the trombones on leben (life). After the soprano frees herself from the chorus on rief (called), the orchestra creates a quiet splendor, with resurrection prominent. The men enter on Wieder aufzublü (to bloom again); soprano and trumpet join to complete the first eight lines of Klopstock’s poem. Mahler omitted the remaining four lines and wrote the rest of the text himself, beginning with the alto soloist’s O glaube, mein Herz (Oh believe my heart), based on the plaintive solos from Part 1 in the English horn and trombone. The music turns insistent as the soprano sings O glaube. Du wardst nich umsonst geboren (Oh believe, you were not born in vain), leading to her agitated duet with the alto about abandoning pain and death.

Suddenly, the altos and men intone the resurrection chorale. The men proclaim: Bereite dich zu leben! (Prepare [yourself] to live!). The organ joins in exalted rapture on Auferstehn, ja auferstehn (Arise, yes...you will arise from the dead). Bells ring out, and the string basses sound the dropping fifth leading to a powerful conclusion.

The meaning of this text is not entirely clear. “[T]here is no judgment [that is, no Judgment Day]…no punishment and no reward,” wrote Mahler in the Dresden program. There is only love and joining with God. There is no mention of Christ here, implying the symphony’s message is not Christian but universal. And what of this text? “With wings which I myself have won...I shall soar upwards...I shall die to live.” The first phrase implies the deceased saved himself, while Mahler scholar Constantine Floros suggests the second may have been suggested by Corinthians 15:36.

The answer may just be that Mahler’s outlook evolved as he wrote this symphony. We do know his views changed radically in his later years. Perhaps the key comes from Ferdinand Pfohl, a music critic and friend of the composer. According to Floros, Pfohl believed that Mahler tortured himself with metaphysical riddles and found comfort in faith in the hereafter. In Pfohl’s words, “the hereafter was the alpha and omega of his life, his art.”

(Sources include Constantine Floros’ Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies; Edward Reilly’s “Todtenfeier and the Second Symphony” in The Mahler Companion (Donald Mitchell & Andrew Nicholson, eds.)

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is the Operations/Personnel Manager). He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. His latest fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

Return to Home Page

|