STRAVINSKY AND BERLIOZ

Notes on the composers and the pieces

Igor Stravinsky

Petrushka (1911)

Hector Berlioz

Symphonie fantastique

Return to Home Page |

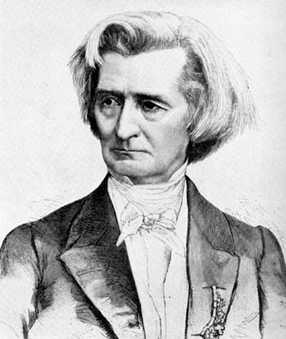

Hector Berlioz

BERLIOZ THE MAN

Louis-Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) was born in France at La Côte-Saint-André near Grenoble. He received an early classical education from his physician father, later taught himself harmony and orchestration by studying scores in the Paris Conservatoire library, and was a fine flute and guitar player. At the age of 12, a crush on 18-year-old Estelle Duboeuf revealed his fiercely romantic nature and anticipated the greater passion that afflicted him 13 years later. His first known formal education was his baccalaureate in Paris, followed by two fairly successful years in medical school, a gesture to his father who wanted him to be a doctor. Music was to be an avocation, but the lure of the Paris Opera and the scores he discovered in the library (especially Gluck in both cases) proved too strong. Berlioz gave up medicine in 1824 to pursue music full-time. After writing Messe solennelle, a piece rich with hints of the future Berlioz, he enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire in 1826. The opera Les Francs-Juges (1826) and Waverly Overture (1827) followed.

Berlioz’s rebellious nature chafed under the conservative strictures of the Conservatoire faculty (only his composition teacher, Jean-François Le Sueur, recognized his genius), and inspiration for Symphonie fantastique came elsewhere. First was English-language performances of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet in 1827 given by a touring company in Paris. Though Berlioz did not speak English, he was overwhelmed. (He later learned the language so he could understand the plays and was a lifelong Shakespeare devotee.) Just as significant was his swoon over Irish actress Harriet Smithson in the roles of Ophelia and Juliet. He stalked the actress for two years, but she refused to meet him. He purged his passion through a romantic relationship with a young pianist, Camille Moke, and the catharsis of composing An Episode in the Life of an Artist in Five Parts: Symphonie fantastique about his obsession with Smithson (1830—the title would be reversed during revisions).

Performances of Beethoven’s third and fifth symphonies by the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire Orchestra in 1828 proved equally revelatory. Berlioz lived in a country with a strong tradition of opera, not symphonies, and he had no idea that instrumental music could be so dramatic and expressive. He had not even heard a good orchestra until he was 17 (at the Opera). Nor had he appreciated the greatness of Beethoven, whom he now heard as a great dramatist as well as a great composer.

The programmatic symphony Berlioz wrote should have made him the brightest star in France’s musical sky. Change was in the air. The July Revolution of 1830 threw out the Bourbons. The trend was against classicism, and Berlioz was part of that trend. But luck ruled against him. A huge storm struck on the night of the premiere, and the hall was almost deserted, though Franz Liszt, who would become a close friend, was in the audience. Liszt’s piano transcription of the Symphonie circulated widely enough for the piece to become at least somewhat known. In addition, Berlioz had just won the Prix de Rome, which stipulated residency in Rome. Despite his contorted efforts to be excused from the residency, he was dispatched to Rome, a city he came to despise. The trip cost him not only a chance to pursue his career in Paris at a critical time, but his (he thought) fiancée, as well. With Berlioz away, Camille’s mother married her daughter to affluent piano manufacturer Camille Pleyel. Berlioz responded by rushing to Paris to kill both Camilles, Mme. Moke, and himself, getting as far as Nice before coming to his senses. He found Nice refreshing and remained a month. While there, he wrote the King Lear Overture and began Rob Roy, which he finished soon after, before returning to Rome. His Italian adventure would have been a complete waste had he not used the time to revise Symphonie fantastique, begin its sequel, Le retour à la vie (renamed Lélio in 1855), write the overtures, and explore the countryside, an experience that infused its way into masterworks like Harold in Italy.

Berlioz returned to Paris in 1832, and the revised Symphonie and La retour were performed that year. The concert was a success, though one must believe it shocked audiences, given Beethoven had been dead only five years and Schubert four. Harriet Smithson was in the audience and was so impressed she agreed to meet its composer. The two were married in 1833. They were happy for a while, but neither spoke the other’s language well, and Berlioz’s idealization of “Ophelia” (whose career was in decline) dissipated with reality. They had a son, Louis, whom Berlioz came to adore, but the couple separated in 1840. Harriet went on to suffer from alcohol abuse and, after an accident, paralysis. Berlioz supported her until her death in 1854.

BERLIOZ THE COMPOSER

Berlioz was at heart a dramatist, for whom form and technique served expressiveness and drama. He wrote five operas, and his four symphonies are instrumental operas. He also wrote overtures, songs for soloist and orchestra (some transcribed), and works for chorus and for chorus and orchestra. Because he could not play the piano, he did not orchestrate “through” that instrument: he composed directly to the orchestra, which is an entirely different mindset. Orchestration to him was as vital as the notes, not something tacked on when a piece was "finished." That idea was new to symphonic composing, but hardly radical to one steeped in a tradition of opera and bands that called for more sounds and instruments than those contained in the symphonies of Beethoven. For Berlioz, employing the harp, English horn, and cornets in Symphonie Fantastique wasa matter of inspiration followed by recruitment.

In many ways his world was the orchestra. He experimented with combinations of instruments and effects, made the orchestra larger, and turned the brass loose. He played with extremes of range and stretched the technique of his players. His Treatise on Instrumentation was studied by many composers and was the foundation of Rimsky-Korsakov’s famous book on the subject that in turn was the basis of orchestral thinking in the 20th Century.

The music itself has tremendous flair and dynamic contrast, ranging from the tenderest lyrical music to loud outbursts and frenzies of activity. Long-limbed melodies with subtle chromatic touches (often emphasizing the minor sixth) rarely conform to four-bar phrases, and harmonies are more about individual chords than progressions. Rhythm is fresh and vital, and it is amazing what he achieves with quickly repeated notes. He was also one of the first to manipulate performance space (for example, the offstage oboe in Symphonie fantastique).

Symphonie fantastique: An Episode in the Life of an Artist in Five Parts

Symphonie fantastique describes the travails of a man suffering from unrequited love who poisons himself with opium, an idea inspired in part by Thomas de Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. Berlioz revised the work extensively before it was published in 1845, and the version we know is far different from the one played at the 1830 premiere. (No score of “1830” exists.)

Some critics consider the work a set of five tone poems. Perhaps, but it does lay out like a symphony, with a rhapsodic first movement that bows to symphonic form with a repeat, a quasi-scherzo, a slow movement, and a vigorous finale. The March can be thought of as an interlude (albeit one with a repeat), but Beethoven set the stage for a five-movement programmatic symphony with his Pastorale. Some conductors believe the repeats break up the drama and omit one or both.

Quotations below are from the 1845 edition of notes describing the symphony’s program that Berlioz wrote for audiences. Movement titles are translations of the French.

“Reveries-Passions.” The quiet but slightly disturbed opening, based on the only extant Estelle Duboeuf-inspired song the young Berlioz wrote, returns the Artist to his unrequited crush on Estelle. The first Allegro (about five minutes in) opens with a cool, slightly aloof 40-bar melody in the first violins and flute that symbolizes Smithson, an ideal woman “who embodies all the charms of [his] Ideal.” Berlioz called it an idée fixe. The theme and the woman it stands for pursue him, reappearing in each movement in an early example of cyclical form. (The theme is from Herminie, Berlioz’s failed entry for the 1828 Prix de Rome.) The Artist’s reverie is accompanied by fits of tears, groundless joy, frenzied passion and jealousy, and finally "religious consolations.”

“A Ball” (attended by the Artist) was originally the third movement and is the only one that uses the harps. The main theme is a beautifully long and spun out waltz. The idée fixe interrupts in the first violins, and later, briefly, in the clarinet before the obstreperous ending.

“Scene in the Country.” This peaceful but troubled section owes much to Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, though its main theme comes from the Gratias movement of Berlioz’s Messe Solennelle. It portrays a calm summer night, with the wind rustling through the trees. Peace, hope and fear of the Beloved’s return mingle in the Artist’s mind. Two shepherds serenade each other with a melody based on a tune Berlioz heard as a child on alpenhorns (an on-stage English horn and an off-stage oboe). The Beloved returns (idée fixe) followed by troubled rumblings in the basses. Toward the end, one shepherd sings but is not answered. A storm sounds in the distance (using four timpani) before solitude returns.

“March to the Scaffold.” The artist poisons himself with enough opium to make him delirious. He dreams that he has killed his Beloved and is condemned to death. The movement begins with a ghostly rumble in the drums and low brass, followed by leaping tubas and loud growls in the low trombones. A raucous march that may or may not have been taken from Les Francs-Juges breaks out in the trumpets and cornets. The Artist stumbles to his execution, witnessed by mocking bassoons and a joyous crowd. At the end, the idée fixe returns in the clarinet—a last vision of the Beloved before the blade falls—and the Artist’s head tumbles into a basket. The final nine chords are the crowd cheering.

“Witches’ Sabbath.” After a spooky opening, we hear a mocking laugh in the trombones. The Artist is at a Sabbath “in the midst of a frightful troop of ghosts, sorcerers, and monsters of every species, all gathered for his funeral; strange noises, groans, bursts of laughter, distant cries which other cries seem to answer.” The Beloved joins the Sabbath, her melody now a grotesque, mocking dance in the E flat clarinet. The orchestra roars in approval, then plunges to the depths. Chimes ring out. (Berlioz calls for high and very low chimes, but the latter are sometimes reproduced by a piano.) Two tubas intone the Dies irae, the famous medieval Latin hymn describing the Day of Judgment. (Berlioz accepted tubas, which make the Dies irae sound nobler than the rougher-sounding ophicléides he preferred.) The movement ends furiously with the Sabbath round dance and the Dies irae combined in a double fugue “that mocks and derides all things religious,” interrupted by giggling witches (bubbling woodwinds) and toward the end by col legno strings (strings playing with the wooden part of the bow) sounding like dancing skeletons.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, Dudley House Orchestra, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is also the Operations/Personnel Manager), and is a local freelancer. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony.

Read about Stravinsky

Return to Home Page

BUY TICKETS

|